Welcome! In this post, we will explore the counter-intuitive nature of probability by studying the famous Monty Hall problem. This problem seems very trivial at first glance, but it exemplifies how probabilities can behave in ways you might not initially expect.

1. Problem Introduction

Suppose you are in a TV show where you may win a car by playing a game. The game is simple: you have to choose among three closed doors. One door has a car and the other two have goats.

The game is played in two steps:

- The host lets you choose one of the three doors, but you do not open it yet.

- The host (who knows where the car is) opens one of the two remaining doors, revealing a goat.

Let’s suppose you chose Door 1. Before opening it, the host opens Door 3, revealing a goat. Now, Doors 1 and 2 remain closed. The host then asks you:

“Would you like to switch your choice to Door 2?”

What would you do? Would you change doors, or would you stick to Door 1? What gives you the highest probability of winning?

Visual Demonstration

If you’re still skeptical, check out this excellent explanation by Numberphile:

2. Python Simulation

We can simulate this game using Python to see if the strategy matters. Let’s define a function that simulates one run of the Monty Hall problem.

import numpy as np

def monty_hall(switch):

# All doors have a goat initially (represented by 0)

doors = np.array([0, 0, 0])

# Randomly decide which door will have a car (represented by 1)

winner_index = np.random.randint(0, 3)

doors[winner_index] = 1

# Participant selects a door at random

choice = np.random.randint(0, 3)

# Host opens one of the remaining doors that has a goat

# (The host cannot open the door chosen by the participant or the one with the car)

openable_doors = [i for i in range(3) if i not in (winner_index, choice)]

door_to_open = np.random.choice(openable_doors)

# Switch logic

if switch:

# Switch to the ONLY other door available

choice = [i for i in range(3) if i not in (choice, door_to_open)][0]

# Return 1 if the final choice is the car, 0 otherwise

return doors[choice]

By running this simulation thousands of times, we can observe the success rates for both strategies.

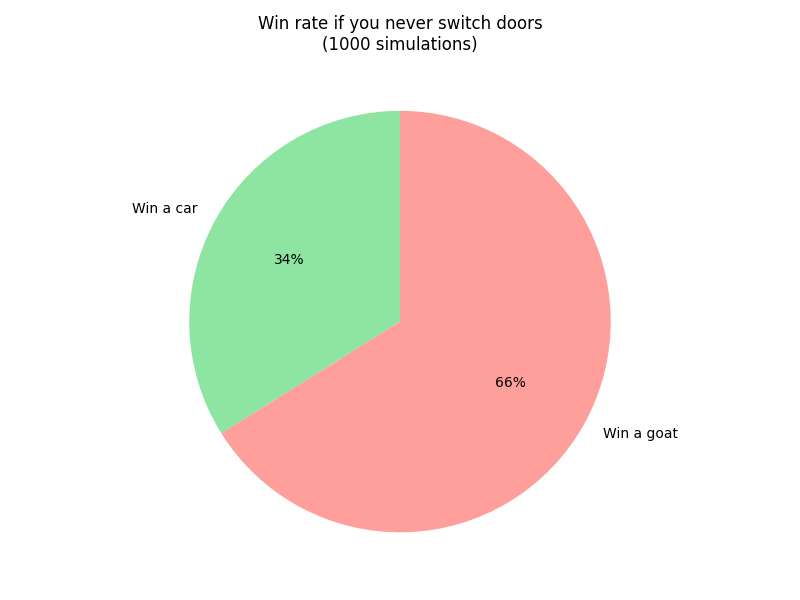

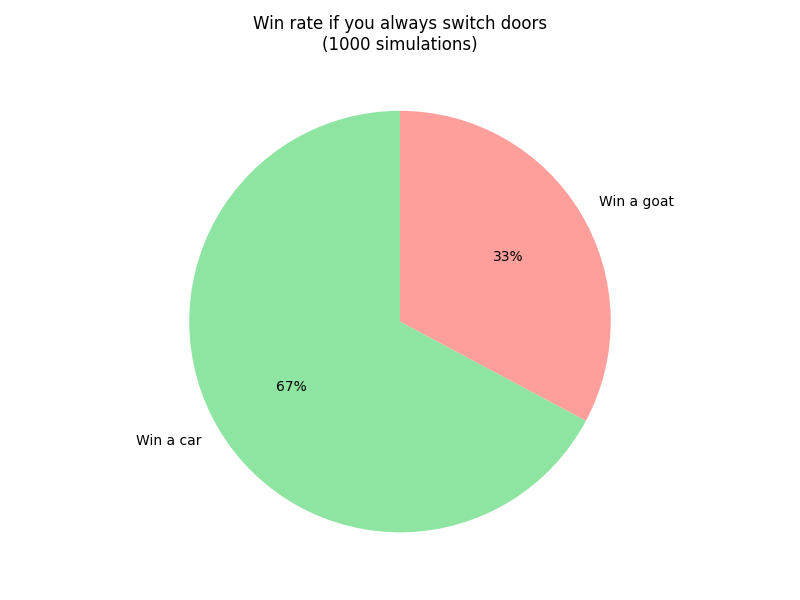

| Strategy | Win Rate (1000 Simulations) |

|---|---|

| Never Switch | ~33% |

| Always Switch | ~67% |

As we can see, switching doors consistently yields a much higher win rate!

3. Analytical Solution

Why does this happen? Let’s break it down mathematically.

Define the events: $E_i$ = the car is behind door $i$ for $i = 1, 2, 3$.

These events are mutually exclusive (the car is behind only one door) and their union covers the whole sample space:

$$P(E_1 \cup E_2 \cup E_3) = 1$$Initially, each door has a $\frac{1}{3}$ probability of containing the car:

$$P(E_1) = P(E_2) = P(E_3) = \frac{1}{3}$$Suppose you choose Door 1. The probability that you are correct is $P(E_1) = \frac{1}{3}$. The probability that the car is behind one of the other doors is:

$$P(E_1^c) = P(E_2 \cup E_3) = \frac{2}{3}$$When the host opens Door 3 and reveals a goat, they are providing new information. They are showing you that Door 3 does not have the car, so $P(E_3) = 0$.

However, this doesn’t change the fact that the initial probability of the group $\{E_2, E_3\}$ containing the car was $\frac{2}{3}$. Since Door 3 is now ruled out, that entire $\frac{2}{3}$ probability “collapses” onto Door 2.

$$P(win | switch) = P(E_2) = \frac{2}{3}$$In short, the host’s action transfers the “uncertainty weight” of the two doors you didn’t pick onto the single door that remains closed.

4. Generalized Monty Hall Problem

What if we have $n$ doors and the host opens $k$ doors?

- There are $n$ doors; you choose one.

- The host opens $k$ doors revealing goats ($0 \leq k \leq n-2$).

- You decide whether to switch.

Simulation

def generalized_monty_hall(switch, n=3, k=1):

doors = np.zeros(n)

winner = np.random.randint(0, n)

doors[winner] = 1.0

choice = np.random.randint(0, n)

# Host opens k doors (not the winner, not the choice)

openable_doors = [i for i in range(n) if i not in (winner, choice)]

door_to_open = np.random.choice(openable_doors, size=k, replace=False)

if switch:

# Player chooses another door from the remaining options

choices = [i for i in range(n) if i != choice and i not in door_to_open]

choice = np.random.choice(choices)

return doors[choice]

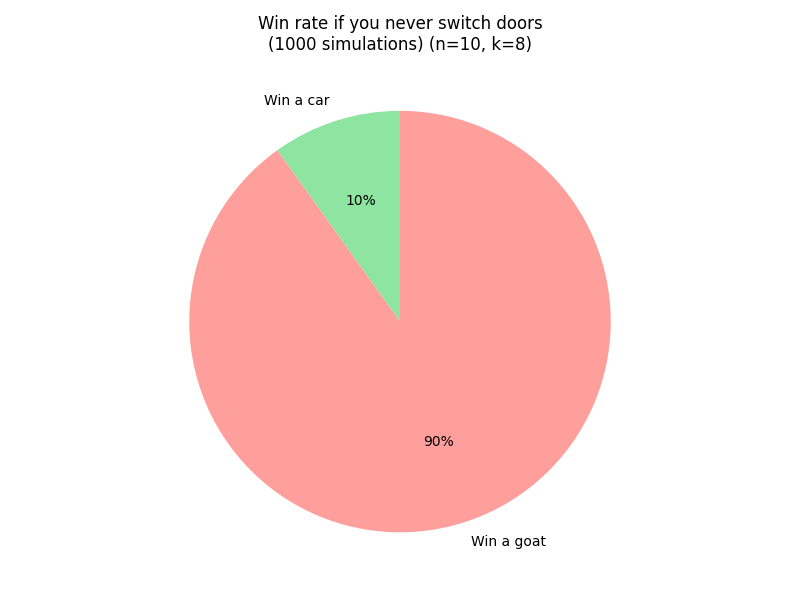

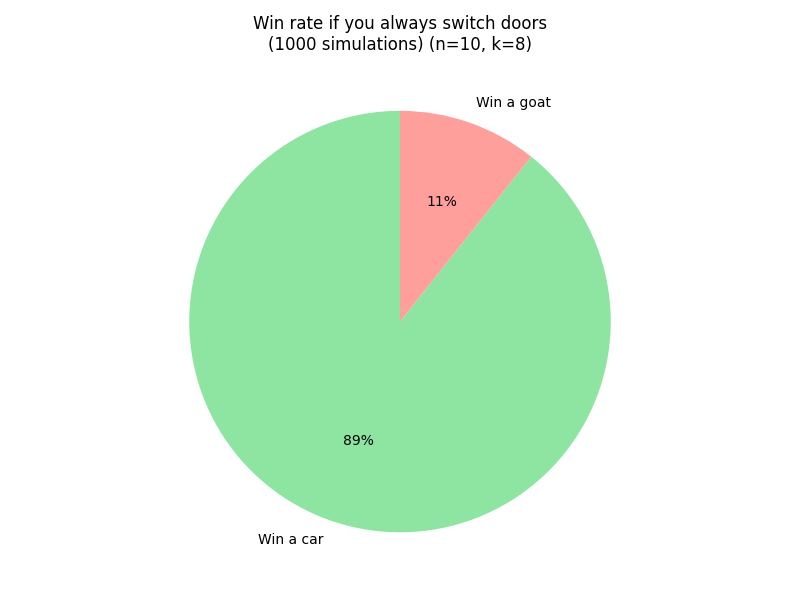

For $n=10$ and $k=8$ (host leaves only one other door), the results are even more dramatic:

Generalized Analytical Solution

The probability of winning if you switch is given by:

$$P(win | switch) = \frac{n-1}{n} \cdot \frac{1}{n-k-1}$$As long as $k > 0$, we find that:

$$P(win | switch) > \frac{1}{n}$$Thus, it is always better to switch doors. Switching allows you to leverage the information provided by the host, whereas staying ignores it.

Conclusion

The Monty Hall problem is a perfect example of why our intuition often fails when dealing with conditional probability. By using simulation and rigorous analysis, we can uncover the truth behind the “trick” and make better decisions!

Congratulations! You’ve mastered one of the most famous paradoxes in probability.